I have to do something so I’m not always lying in bed taking pills

Iveta Horváthová (1967) is only in her ID. He signs his drawings and paintings as Rimini Filli.

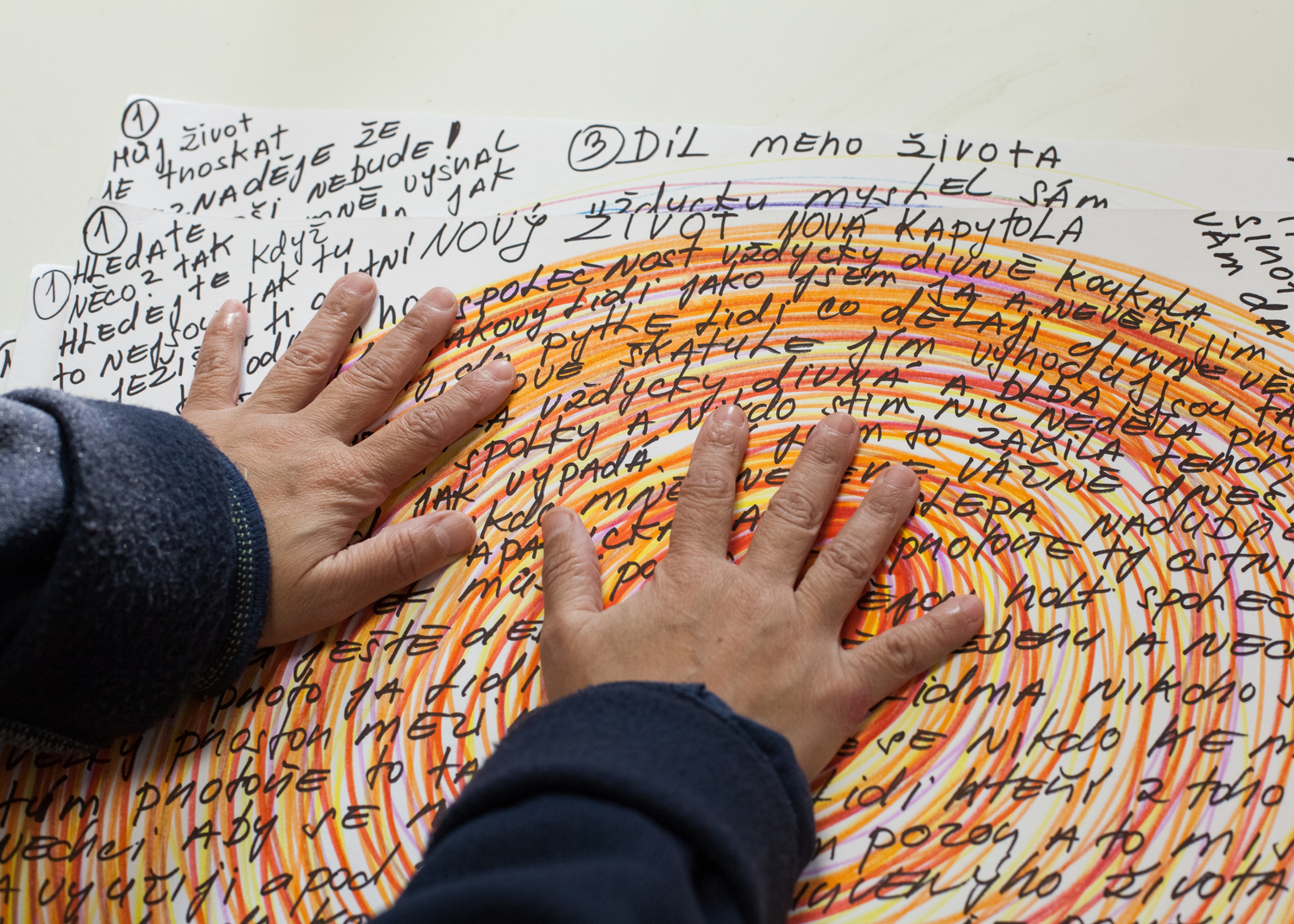

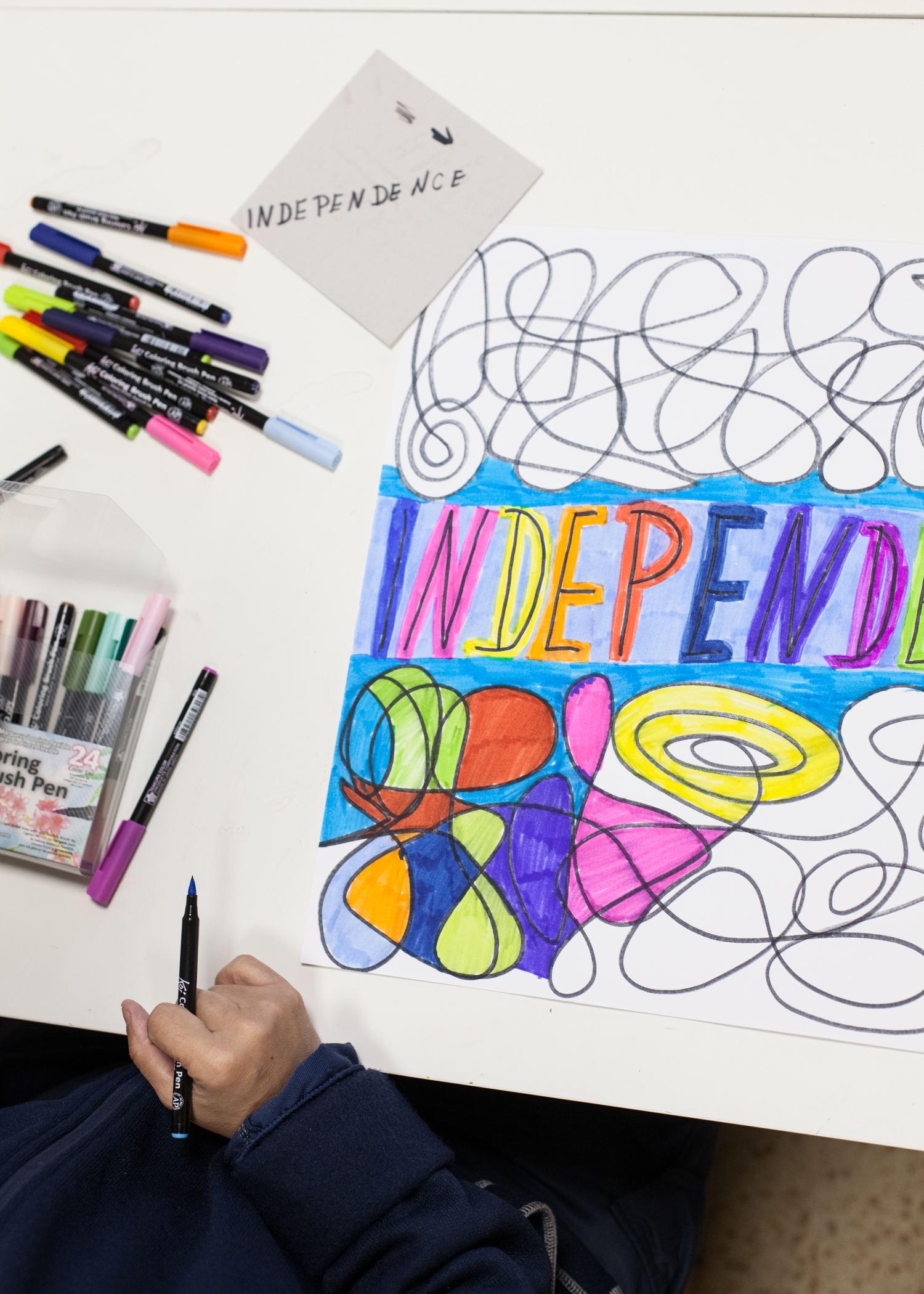

She talks openly about her childhood between her own family and children’s homes, bullying at school, life on the street, her experiences with psychiatric hospitalization, and functioning within the Roma community. In her drawings and paintings, she focuses mainly on portraits – geometrized or otherwise stylized heads, sometimes depicting Iveta herself in various states of mind, sometimes a circle of her acquaintances and friends, fairy tale characters or politicians (e.g. drawing of Donald Trump in 2030, etc.). At the same time, she is the author of several “fairy tales for adults”, in which fairy tale characters get into real situations: they run away from home, have health and existential problems, experience various stressful situations, but also, for example, go on excursions to Mars.

Her dream is to go to Crete or Cyprus, where she says she originally comes from. But she doesn’t have the money for the trip yet.

In 2006 her works were included in the exhibition Art Brut – Collection of abcd in the Stone Bell House. Currently she works at the Studio of Joyful Creation in Prague, Letná.

You speak very openly about your childhood. Can you say something about growing up in orphanages, school or your short stays “at home”?

I grew up in an institution almost from birth until I was 20. From the age of one until I was six I was in two nurseries, and then from the age of six I was in an orphanage with the big kids. I was there under the communists. A lot of bad things happened there that I don’t even want to talk about, both in the family and in the school and in the orphanage. They mistreated the children. And my parents treated me badly too. Some of that stuff is still in my head. I want to throw it away and forget it, but I can’t, it keeps coming back and it keeps reminding me of the bad past. I was bullied and discriminated against at school, people there treated me really bad. Sometimes it was, I’m sorry to say, a bit of a shame. I was also bullied by kids there because I was a gypsy and bad things happened to me. The teachers there were psychopaths who beat up the kids. I was relieved when I left.

You were sent home several times, but you always came back quickly…

I’ve been home all of four times, and only during the holidays. I went home, and it was my revenge, I won’t tell you how. Just both parents are paedophiles, so let everyone figure out what that is. I ended up having a plan to kill them, murder them. So I imagined – in those eight, nine years of mine – how I was going to murder them, how I was going to eliminate them, the whole family, how I was going to kill the family, how I was going to quarter them, dismember them, throw them in a bonfire and disappear in the English way. That’s how I planned it. And when the day came to do it, I said, “How the hell am I gonna do this? How am I gonna do this? How do I do it? How do I do what? How do you do it? Well, I thought, “I’ve got an axe, I’ve got a fire, I’ve got a fire. But where can I get rat poison? I’d throw it in their food, they’d all eat, fall over and be dead. That’s what I was most worried about. I kept thinking about it and thinking: This is probably going to end badly. Or, “Is this gonna go badly with me? So I’d rather pester people on the street and tell them: You want to adopt me? Take me home, I can’t go back. And people would look at me and say: You have to go up there, up on the hill, there’s social services on the hill, there’s curators, so go there and they’ll help you. I thought about it, but I didn’t know: where is the social services, where do I look for them? I was nine years old! So I went to the hill and what do I see: a house as big as a cow, but nobody in it. So I thought: Well, that’s nice, so I’m going to sleep outside tonight. I don’t have a tent, I don’t have a sleeping bag. They went home, and now what? I can’t go home now, I closed the door. And then, suddenly, the lady came, the social worker, and she said: ‘Ivetka, for God’s sake, what are you doing here? Who are you waiting for? And I said: I’m waiting for you. And she said: And why? When I told her all this, she looked at me and said: What are they doing to you? What are they doing? And then she took me somewhere, to some institution that was somewhere nearby, and I spent three Sundays there. Then the social worker came and said: Today we’re taking you to the children’s home you were in before, so you’re going back there. Your mother’s nice…

I was only wearing a shirt, panties and tights, even though it was cold.

So they put me in a 613, the car the communists used. When they returned me to my home, everyone looked at me and said: Jesus, what are you doing here, Iveta? The nurses didn’t understand, and neither did the children. And I went to bed and for a long time I didn’t know what was happening to me. I was delirious, I had a fever, and I don’t remember how I got to the hospital. I don’t know where it was, how long I was there, what they did to me. I don’t remember at all.

What was the school like within the orphanage?

I came back from the hospital and started 5th grade. I was not good at learning, I was not good at it. Just the art. I was failing everything. In 8th grade, I found myself, I don’t know how. But there was a teacher, a bastard who beat up kids just because they didn’t know math or Czech. And he saw them as bastards. He said to me: Well, Horváthová, you’ll end up badly and you’ll be in jail any minute. You’ll go to jail and they’ll give you a string and you’ll be dead. So he gave me all B’s from top to bottom and one F in math. And when you called the kids to the board, they stood there like convicts when you looked at them. I got hit in the face with a ruler just because I had mistakes in my book. After that, I don’t remember much, it’s all kind of blown out of my head. I just felt the kids bullying me, hurting me. I wished I was big enough to leave.

What was the transition from the orphanage “out there” as you call it?

I was in a home back in the communist era. They drilled their stuff into our heads, but they found people to do it who did nothing but bad things to the kids there. They abused them, tortured them. I just wanted to leave, but I had nowhere to go. So they just took me to Náchod and told me: stay here, do what you want, go to work here, study and so on. I had to go to work. They made a big deal out of me for not going to school. They ruined my life. Communists, or whoever made that up. That I wasn’t going to school anymore, that I was going to work.

When I left the orphanage, I had no support. I lived in a dormitory. I was there for three years and I went to work at the same time. There was a factory, a textile factory right nearby. I had to go there from six o’clock and clean cloth. Because it was a mess, so I was always cleaning, and then it went on and on inside the factory, and then it was exported and taken away. We used to smell gasoline all the time. And there were cockroaches. And communists. I told them to fuck off. I told them: I’m not a comrade. I’m 16 and I’m still a child! And they looked at me and said: Yeah, she’s weird. Being there all day and working and looking at those women working there and being torn up both mentally and physically, and being there with them… It just wasn’t nice. I didn’t have any friends there.

So that was the transition. When I was 19, I went to a company hostel and I was there until 1991.

Have you ever thought about what should be different, what would you change?

I would abolish orphanages. No, or I’d keep them, but I’d change them in that it would be in the form of some aunts and uncles. That one aunt and that one uncle would have, like, seven kids, and they’d take care of them. Kind of like foster care. And they’d find them maybe a place to live, a job. It’d be a more friendly and relaxed environment. It’s a shitty system set up by the state, but the conditions for the kids aren’t good either. When they send the kids out, they have nowhere to live and they can’t do anything, not even calculate their pension, let alone their wages. They’ve never worked, they’re not ready for anything. They’re locked up in that orphanage, cut off, nobody teaches them anything, and then when they go out, they get lost. Our orphanage is a wreck now. They tore it down and they’re doing something else.

You’ve had to live on the streets several times. How did that happen?

The factory in Náchod closed down. I moved to Prague and I stayed here, but I had no support or finances. I couldn’t find any work and ended up on the street. I was living in different Hope and Salvation Armies, but I had no money, so they kicked me out. I avoided people, I wasn’t comfortable. I was always thinking about what I was going to eat, that I couldn’t even take a bath, where I was going to sleep. But I told myself that I would do something about it, that I could take care of myself, and finally I found a job in Motol as an orderly. But it was hard work, with very sick children. I collapsed from it.

Then I went to the psychiatric ward, and then back on the streets. I developed schizophrenia, paranoia. It came out when I was 20, and then I just had to treat, treat, treat. And pills, pills, pills. There was nothing I could do about it. And then one day I just had to take a razor blade and cut my vein and I was done. It was hard. Because of my past. Also because you’re a woman and you’re on the street. But I wasn’t the only one who ended up on the street. Everybody ended up there, people from the orphanage who didn’t get housing and ended up there with nothing. Then I found housing in Žižkov, where I was from 1996 until 2000.

Are you getting any support?

I have a third degree disability pension, so full pension, since 1996, 22 years. So far, I’m not acting like a fool, I’m keeping a cup, managing to live on my own. I’m alone in my room. I’m in Hope, but I live alone. But in a year, I’ll go away again, somewhere else, to another Hope. So I don’t really have a permanent home: they move us to wherever there’s space. I don’t have any hope for any social housing. So for the rest of my life, I’m just going to be bouncing back and forth between the Salvation Army and Hope. Twice here, three times there, and again, back and forth for a while. It’s so nicely set up that homeless people only get a year’s housing, they don’t qualify for social housing. They have to take what they’re offered. And I’ve lived in Prague for 22 years, so I can’t afford it, I can’t get it. They just don’t care if I’m on the streets, they can’t do anything about it. And I don’t have the money to go to a hostel. I’d have to be a millionaire to go to a hostel. And on top of that, it’d be living two to a room, and I don’t want that, I can’t do it.

Do you know anything about your parents, your siblings?

I know I have seven siblings, but I don’t even know their names. They don’t remember me, and I don’t remember them because they either weren’t born yet or they were very young. I’m the only one who was in an orphanage, and my parents took it out on me. Because I have a cleft just like my mother, she decided to beat me. My parents did nasty things to me and didn’t do anything to my other siblings. That was my punishment for being born. My father later died in jail because they found out what he did to me, they investigated it. He was quite a pig, so they locked him up. And my mother played the fool, that she was nothing, that it was all her husband, so she got away with it. And the communists let her down pretty good.

Do you dream about the things you’ve been through? Are you getting into your dreams?

I’m a bad sleeper in general. I’m on pills, three pills. There was a time when I was taking, like, ten sleeping pills a day. Mostly I dream things that have no head or tail. I always look out the window the next day and think: What the hell was I dreaming about? One time I dreamt a lot about snakes, there were snakes everywhere. And the doctor told me it might mean there was something wrong with my sexuality. That someone was stalking me, that someone was trying to kill me, and that it was connected to sexuality, family, school, that kind of thing. And that the snake symbolizes something from my childhood. And then I also used to dream a lot about my family. Someone always came and said: I saw your family, over there and over there. And then someone else. I always went there and waited, but nobody ever showed up.

Do you dream about the things you’ve been through? Are you getting into your dreams?

I’m a bad sleeper in general. I’m on pills, three pills. There was a time when I was taking, like, ten sleeping pills a day. Mostly I dream things that have no head or tail. I always look out the window the next day and think: What the hell was I dreaming about? One time I dreamt a lot about snakes, there were snakes everywhere. And the doctor told me it might mean there was something wrong with my sexuality. That someone was stalking me, that someone was trying to kill me, and that it was connected to sexuality, family, school, that kind of thing. And that the snake symbolizes something from my childhood. And then I also used to dream a lot about my family. Someone always came and said: I saw your family, over there and over there. And then someone else. I always went there and waited, but nobody ever showed up.

When did you start drawing, when did you become interested in it?

Third grade. I drew a doll from a reading book that was on the front. The book was just kind of plain, nice but simple pictures, colorful. But you could draw from it. I drew it and took it to my teacher to keep it safe at home. And she took it home and hid it for me. I also went to different painting competitions and I was lucky enough to always win. But the kids were jealous, and when I got my present, they ruined it.

Then you used to paint in a studio in Bohnice. It seems that you started to paint more only there, because the conditions were there. How did you get there?

When I first got to Bohnice, they told me, “Hey, there’s a painting studio over there on the fifth floor, go and paint something. So I started to go there and every time I was in Bohnice, I would go there and paint. There was no assignment, no strict guidance. I could just come and paint. The doctor told me then that I had a talent and that I should stay with it. But I decided that I wasn’t going to do it every day, but only when I enjoyed it.

I’ve changed a lot of doctors since then. Now I have a doctor who normally treats old age dementia, and she also treats me with my schizophrenia, which is ridiculous. But that doctor took me in and she’s been good to me. Her name is also Iveta, she’s about 40 years old. We always talk about everything, well, not everything, but we talk. The last time I was in Bohnice was in 2014. I swallowed pills. I don’t want to go back, the doctors were terrible. I just told myself I’m not going back. There was a doctor who labeled me a psychopath. She said I was dirty, that I liked to fight, that I was psychotic, that everybody around me was suffering and stuff like that. She wrote it about me to the court. I told my friend and she said: Don’t worry about it. They just like to label people and treat them accordingly. And then they treat them according to what box they’re in. And according to the doctor, I’m a born psychopath, even though I told her I wasn’t, that I’d been through something when I was younger. But the doctors don’t believe me and look at me stupidly, and that’s what the treatment is based on.

How’s the painting going now?

I work when I feel like it. Sometimes I don’t paint for half a year or even a year. Now I don’t feel like painting either, but I thought I have to do something, so I don’t just lie in bed at home and take pills. I come here to the studio once a week. When I’m not here, I’m at home. I get up and I walk, I go for a walk. I go to the mall to see what’s nice, and then I buy something, and then I go home. When I feel like it, I come here. I used to paint at home, not so much now. And I only write when I’m in the mood.

What does your pseudonym Rimini Filli mean? Why did you decide to use it?

I made up this pseudonym so I wouldn’t look like an asshole at exhibitions. Because there are so many Horvaths, eight thousand of them all over the Czech Republic, and I didn’t want to have a name like that. How would they pronounce it then, right? Horváthová… What’s that? So I decided to give myself a new first and last name. And I knew there was a town in Italy, Rimini, and it was on the water. So I thought I’d call myself Rimini. And the other one, the last name, I thought about for a long time, and Filli is like… It doesn’t mean anything, Filli is nothing. It’s not even a stolen name from anybody. I know Emill Filla was a painter too, but I really have nothing to do with him, this guy who died and sells paintings for millions. So that’s how I put it together and it’s stuck with me. People say it’s really good for exhibitions, rather than some Horvath. That it has an exotic quality to it and that it’s easy to pronounce and remember. Some artists have surnames that people label them by. I was pleased with myself for being a clever girl who could make up a name and a surname, and one that didn’t tell if I was a man or a woman, it was just vague, mysterious.

What are you working on now? Do you have your latest work here?

I just started painting pictures like sphinxes. It’s because I’m drawn to Egypt, as if I’m living there, or have been there in the past. There are specific people in my paintings, maybe even people from here. I always write something at the bottom, the person’s name and stuff. I’m doing a series of heads now. Some are from here in the studio, others from public life. Like Zeman, what he’ll look like in 2030.

A lot of people ask me why I don’t paint my depression when I’ve been through so much. Why don’t I paint it? I have a simple answer: because I’m not good at it.

When I paint, the person in front of me is not sitting there. Maybe I see someone here or on the street, and then I paint them as I remember them when I’m home alone. He doesn’t have to sit for me as a model. That’s something unnatural to me: one who is painting it and the other who is just sitting there… I don’t have to do it that way. I look at these people and then I go home and paint them so that it’s them, but at the same time in a different form, like a sphinx. But it’s still them.

Do you feel part of the Romani community? Do you have friends in it? Do you feel supported by them?

It’s problematic. I recently met my sister, whom I haven’t seen in 40 years, and she says my mother is blonde and that she turned black. We have it half and half, my mother is white and my father is a gypsy. I’m such a mix, such a blur. So, I don’t classify myself as a gypsy, I don’t even talk to gypsies, I don’t seek them out. It’s more like they look up to me.

I wanted to get into a Romani school, but I was told I wasn’t Romani because I didn’t speak the three main languages. I don’t look it, I grew up somewhere… So I’m not a gypsy. It’s a form of bullying and discrimination that they didn’t want a person like me there.

Outside, people look at me badly, but here I have a background, I have friendly relations. I have white friends outside. But this past Saturday, my friend got mad at me because she called me a hypochondriac. She said I think too much about things and I suggest things to myself. So I left her and deleted her address and phone number. And that was it.

One of your exhibitions was called Double Personality. You talk about your personalities, you’re aware of them. What do these two personalities look like, how do they differ and how do they live together? In what ways does the other one manifest itself and when does it surface?

I have, like, two identities. One I know nothing about. But a lot of people tell me: You don’t look like a gypsy, you’re a foreigner from somewhere in the East. They say I should find out and get DNA. But I don’t have the money, it costs at least 10,000. People often don’t know what to make of me. A lot of people tell me I have an alien cuckoo face, a very mysterious face. My intuition tells me it’s probably true, that I’m some kind of foreigner. There’s one island in the Mediterranean that attracts me the most, and that’s Crete. So I started telling people when they kept asking me if I was from Crete. Or Cyprus. It’s like it’s my home, I’m so drawn to it. I want to go there, but I still don’t have the money for a plane ticket. Or a ticket, even though it would be a long bus ride.

Somehow I long to be there, to go there, to experience something there, or to paint the people there, who are all nice and friendly. I’d like to meet them and maybe have a holiday together. Or meet my family there. I don’t know if I have anyone there or not. But my intuition tells me that I probably do. I’ve never really looked into it, but people come up to me all the time and say, “Hey, you’re Spanish. Or, “You’re from Mexico!

One of your exhibitions was called Double Personality. You talk about your personalities, you’re aware of them. What do these two personalities look like, how do they differ and how do they live together? In what ways does the other one manifest itself and when does it surface?

I have, like, two identities. One I know nothing about. But a lot of people tell me: You don’t look like a gypsy, you’re a foreigner from somewhere in the East. They say I should find out and get DNA. But I don’t have the money, it costs at least 10,000. People often don’t know what to make of me. A lot of people tell me I have an alien cuckoo face, a very mysterious face. My intuition tells me it’s probably true, that I’m some kind of foreigner. There’s one island in the Mediterranean that attracts me the most, and that’s Crete. So I started telling people when they kept asking me if I was from Crete. Or Cyprus. It’s like it’s my home, I’m so drawn to it. I want to go there, but I still don’t have the money for a plane ticket. Or a ticket, even though it would be a long bus ride. Somehow I long to be there, to go there, to experience something there, or to paint the people there, who are all nice and friendly. I’d like to meet them and maybe have a holiday together. Or meet my family there. I don’t know if I have anyone there or not. But my intuition tells me that I probably do. I’ve never really looked into it, but people come up to me all the time and say, “Hey, you’re Spanish. Or, “You’re from Mexico!

You’ve been diagnosed as schizophrenic and mentally ill. What does that mean for you?

Dual personality. I have schizophrenia, paranoia, I see and hear things. I look like I’m perfectly normal here now, but when I walk around people, I feel like I have a split personality. I hear people talking weird and I don’t like it. Or they look at me funny or they think something weird about me. When I’m on the subway, everybody’s staring at me. They look at me weird and I don’t know what to think. Or they want me to talk to them, but I don’t have time. Some are quiet, shy, they want to talk to me, but they don’t say anything. And I’m quiet and shy too, so the conversation doesn’t happen in the end.

The thing about this dual personality is that one minute I seem normal and the next minute I seem… well, abnormal, I guess. I’m always in my head, and then I don’t know what to do. One personality is good and the other is bad. The bad one tells me: Hey, do this and do that, like jump in front of that car… The other one says: Please don’t be stupid, what are you doing? You’re painting pictures! You’re painting pictures! And I still don’t know what to do. I don’t want to go to the psychiatric ward, because those stupid doctors don’t believe me. Nobody believes I’m paranoid, and everybody says, “She’s normal, she doesn’t have paranoia, because if she did, she’d be pretending or acting differently. And I don’t. I’m not acting out at all, so nobody believes me. But I’ve been labeled a psychopath, and I’m weird, and all that stuff. I don’t like that, that kind of labeling. I don’t think I’m such an idiot that I’m gonna let these doctors get away with it. Or from people who take care of people who have mental illness. I want to be taken seriously, but unfortunately I can’t. I mean, people here take me seriously, but when I go out, it’s bad. Basically, I’ve been labelled since I was a kid. One day I’m like this and the next day I’m like that.

Do you have an unfulfilled dream? Something you’d like to make happen?

My dream is to get to Crete. Buy a proper camera and take pictures of the people there. The grandmothers, the grandfathers. And then paint them.Thanks to Johana Pošová and the Studio of Joyful Creation in Prague Letná.

Realized with the financial support of the City of Prague and the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.